ASEAN’s Mixed Bag

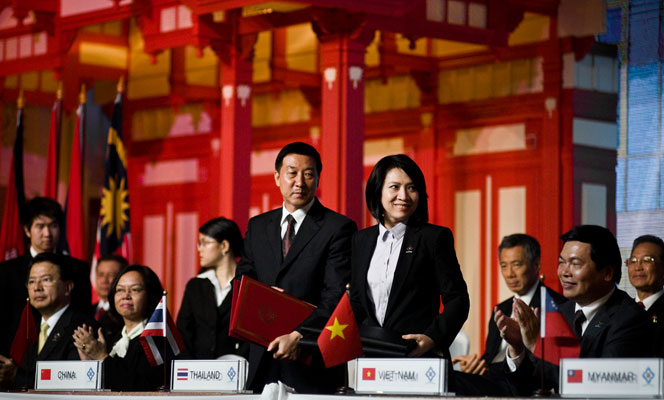

Image: Thaigov

Image: Thaigov

The Diplomat speaks with IISS-Asia head Tim Huxley about ASEAN’s successes, failures and prospects for a regional community by 2015.

ASEAN member nations have pledged closer integration, including forming an ASEAN trade community by 2015. How likely would you say they are to achieve this?

I think the problem with ASEAN is that for all its strength in some areas–and it has made some progress in terms of economic integration–that it’s still a grouping of states that have very diverse political systems, ranging from fairly successful experimentation with democracy in Indonesia’s case, through to a military authoritarian state in the case of Burma (Myanmar) or socialist authoritarian states in the case of Vietnam or Laos and absolute monarchy in the case of Brunei. So it spans the whole spectrum in political terms, and that means it’s actually hard to build co-operation that’s based on really far-reaching, common norms and ways of behaving in political and social policy.

So although ASEAN has set out various types of communities that it wants to establish by 2015, including a political security community and a socio-cultural community and an economic community, I think it’s going to be in the economic sphere that it does rather better and it’s not going to do so well in the other spheres. Given that the target is only six years away, it’s hard to see what sort of political community, in particular, it could establish. I think there are many people who are sceptical about this and there are some within ASEAN who have started to really raise questions in a direct manner about ASEAN’s ability to forge deep co-operation in the social, political and security spheres.

Closer security integration is often seen as lagging closer economic ties. What’s holding back closer security co-operation in ASEAN’s case?

I think the fundamental point is that these states have such diverse political systems that until you have some kind of common norms and values in your domestic social and political systems it makes it very hard to co-operate regionally and internationally in any profound way. You see the world in different ways, and your people are unable to relate from the basis of common understandings about how societies and political systems are organized. That’s the difference between Southeast Asia on the one hand and Europe on the other–in Europe we have that basis and we set certain requirements–fairly strict requirements–for potential members in terms of social and political systems. ASEAN, in contrast, has worked on the basis until now of states in that geographic area, whatever their domestic systems, being allowed in. So it’s a completely different set up.

A related question is that these states, at least in their modern forms, are fairly young in some cases and a number of ASEAN’s members including Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Vietnam, Laos–basically all the members apart from Thailand–are post-colonial societies. And one inheritance from the colonial era has been disputes among them, particularly territorial disputes, which they have yet to work their way through. So the result of these various factors is that there’s considerable suspicion and sometimes animosity between ASEAN states. And I think a worrying thing we’ve seen over the last few years is that the role ASEAN seemed to play in its earlier years as an institution that helped mediate tensions among its members seems to have atrophied–the existence of ASEAN doesn’t seem to have imposed the same sort of restraints on its members behaviour as it did maybe 10, 15 or 20 years ago. So in recent years we’ve seen quite serious border disputes and other tensions between members, for example between Thailand and Burma, between Thailand and Cambodia, between Indonesia and Malaysia and sporadically between Malaysia and Singapore. So ASEAN doesn’t seem to be doing well at one of the key things it was set up to do in the first place.

Why do you think ASEAN is failing in this regard now?

I suppose one important factor is that with the end of the Cold War, the existence of an outside threat on which ASEAN governments could to a greater or lesser extent agree was removed. And where in the past that threat encouraged them to hang together or hang separately, that sense of outside threat, in the form of communism, no longer exists. And they haven’t coalesced around any new external threats. For example, China is not seen generally by ASEAN as an external threat that requires them to band together.